2025

- ×

- ×

- ×

- ×

- ×

- ×

GIBCA #13 a hand that is all our hands combined

at Gothenburg , Sweden (20/09 - 30/10/25)

Georgia Sagri, Gone Gone, Beyond, 2025, Fabric, polyester, permanent blower, guy ropes, bag, 4.9m x 2.7m x 2.7m GIBCA #13, Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Ellika Henrikson ©Georgia Sagri

Georgia Sagri, Gone Gone, Beyond, 2025, Fabric, polyester, permanent blower, guy ropes, bag, 4.9m x 2.7m x 2.7m GIBCA #13, Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Ellika Henrikson ©Georgia Sagri

Georgia Sagri, Gone Gone, Beyond, 2025, Fabric, polyester, permanent blower, guy ropes, bag, 4.9m x 2.7m x 2.7m GIBCA #13, Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Ellika Henrikson ©Georgia Sagri

Georgia Sagri, Gone Gone, Beyond, 2025, sculpture and performance, 20 September 2025, GIBCA #13, Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Ellika Henrikson ©Georgia Sagri

Georgia Sagri, Gone Gone, Beyond, 2025, sculpture and performance, 20 September 2025, GIBCA #13, Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Ellika Henrikson ©Georgia Sagri

Georgia Sagri, Gone Gone, Beyond, 2025, sculpture and performance, 20 September 2025, GIBCA #13, Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Ellika Henrikson ©Georgia Sagri

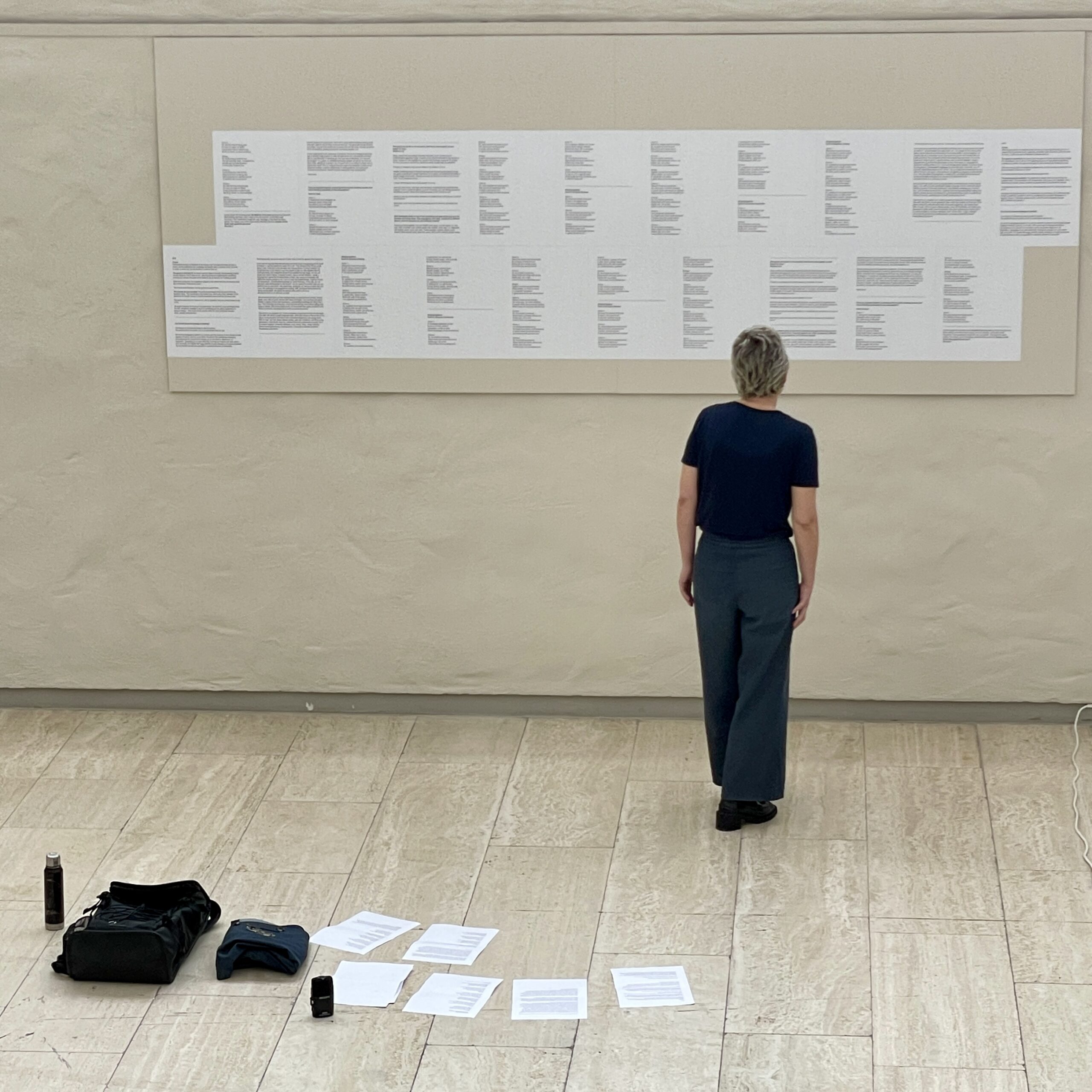

Georgia Sagri, City (2024), 2025, HD video, 40 min., 10 posters, inkjet print on paper, Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Andrej Lamut ©Georgia Sagri

Georgia Sagri, City (2024), performance, 21 September 2025, 40 min., Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Andrej Lamut ©Georgia Sagri

Georgia Sagri, City (2024), performance, 21 September 2025, 40 min., Röda Sten Kunsthalle, Gothenburg. Photo by: Andrej Lamut ©Georgia Sagri

Public Secrets

at The Breeder, Athens (21/06 - 30/08/25)

The Cynics Republic – Plac Defilad

at Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw (10/05/2025 - 08/06/2025)

Georgia Sagri, SALOON: There Is No Country In Our Hearts (2014), HD video, sound, 73'28", MSN Warsaw. ©Georgia Sagri

Kore

at The Breeder, Athens (08/05 - 07/06/25)

Kore, installation view. Photo by: Nikos Katsaros. ©Georgia Sagri

Kore, installation view. Photo by: Nikos Katsaros. ©Georgia Sagri

Kore, installation view. Photo by: Nikos Katsaros. ©Georgia Sagri

Kore, installation view. Photo by: Nikos Katsaros. ©Georgia Sagri